PUBLISHED: September 2023 By Ethan Placke, HPB Conservation Technician

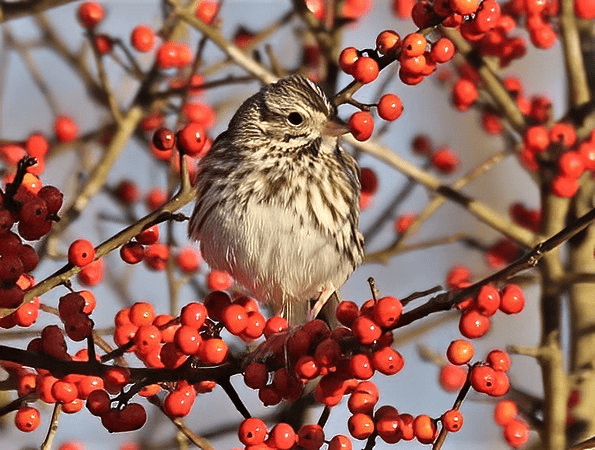

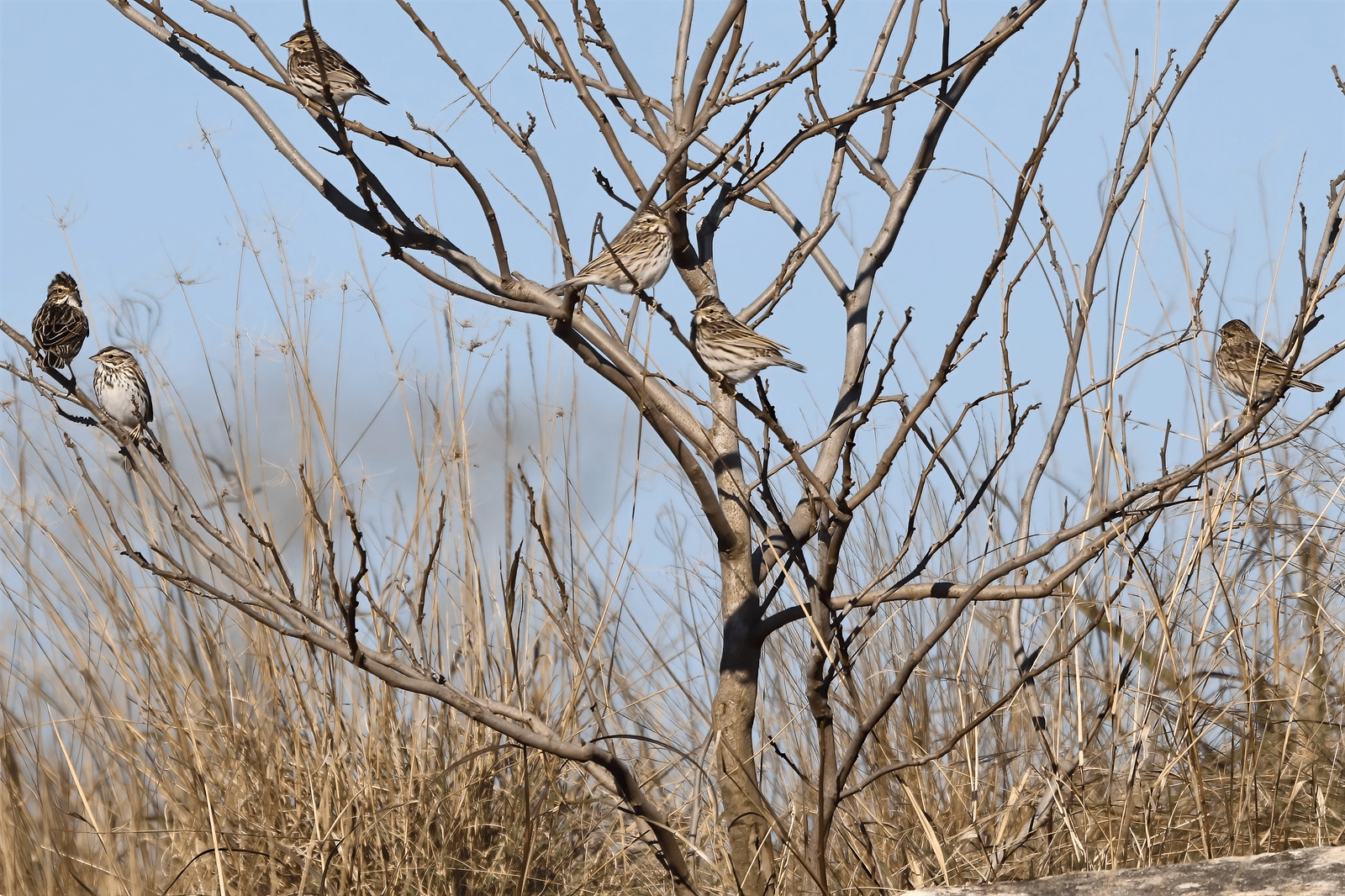

With over 500 species of bird that migrate through the Houston area, one can expect to find quite the dazzling variety when going out for some birding. Some species will be up in the trees of our forested areas, while others may choose more urban trappings for themselves. Others will be found in and around our grassland areas, and it will be a small group of three of these grassland-dependent birds that we’ll look at today.

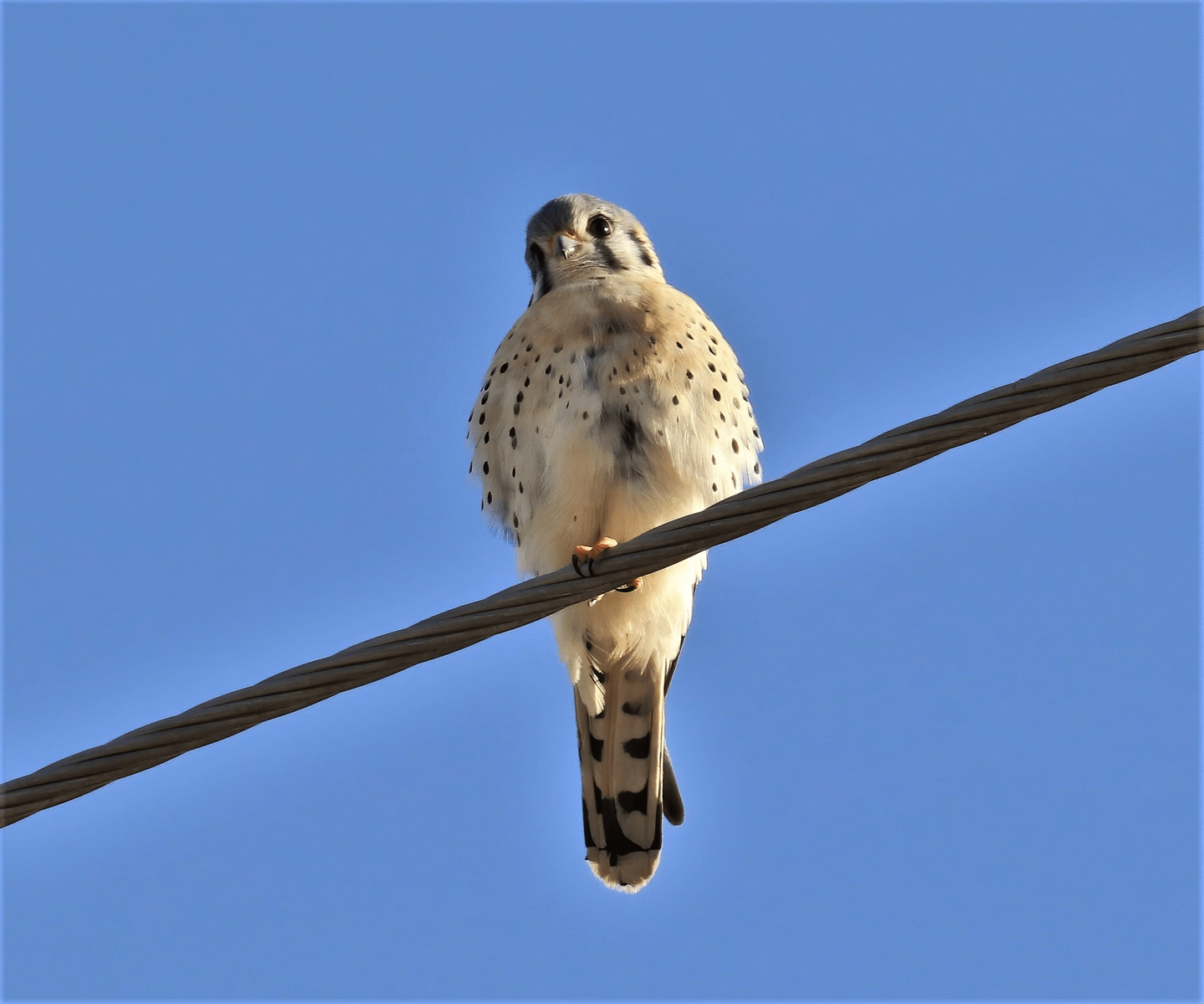

Perched up high along a telephone wire or maybe a dead tree in the open, if one has a sharp eye, they will be able to see the smallest falcon on the continent; the American Kestrel (Falco sparverius). Pumping their red tails as if to keep balance in the breeze, these sharp eyed, tiny balls of predatory instinct will survey all around them for a glimpse of a potential meal on the ground. A quick swoop to the ground is often all it takes for these predators to subdue their prey, which could be anything from a large insect, a songbird, a woodpecker, or even a squirrel!

While these raptors are considered to be a low conservation priority, estimates indicate we have lost approximately 53% of their populations between 1966 and 2019. This is almost entirely due to habitat loss from clearing of forests and removal of dead trees for construction. Farming practices that remove brush cover also contribute to habitat loss for this species. Insecticides also negatively impact this species by reducing the number of invertebrates they can hunt.

Though they rely on grasslands to hunt, they need tree cavities to nest, which they cannot make themselves. In some areas the establishment of properly constructed, and placed, nest boxes has been a needed boon to the population, but in the future it may be nearly impossible for us to see these enigmatic little American predators swoop down to catch our next bird; the European Starling.

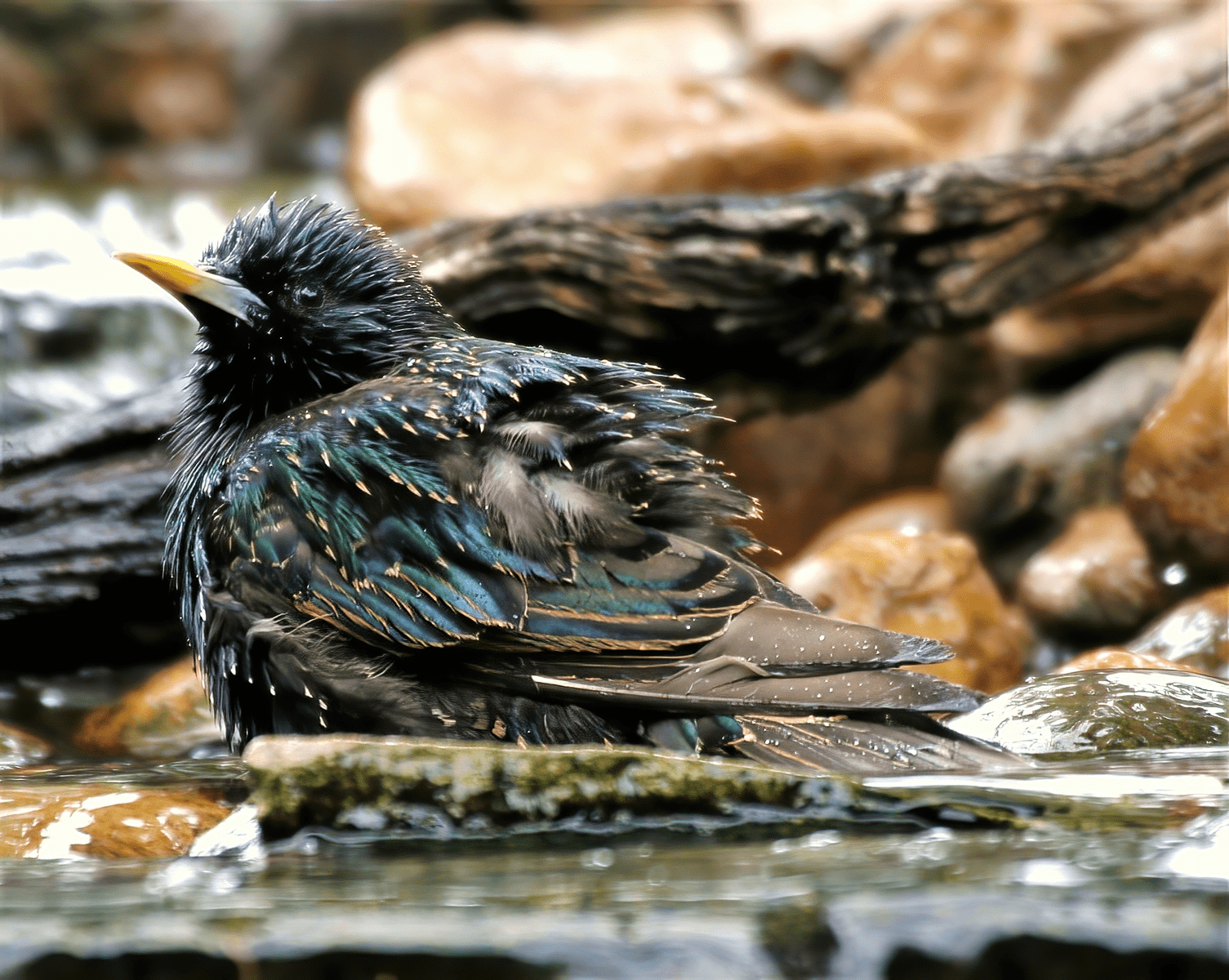

A species introduced in the 1890s by a group of Shakespeare enthusiasts so North America would have every bird mentioned in his writings, the European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) is now one of the most prolific songbirds on the continent. They are doing very well for themselves as the original population of about 100 has spread into one of an estimated 250 million and appears to have seen little to no negative impacts from their low genetic diversity.

These little black birds are admittedly pretty to look at and are fun to watch as they move in little zigzag like patterns on the ground while foraging for insect prey in the grass. This species is very common to see in urban lawns as well as in more rural fields, and I’m sure is one that we have all seen plenty of times.

While they do forage in grasslands, Starling, like Kestrels, need cavities to nest. Like Kestrels, they are also incapable of creating these on their own and rely on woodpecker cavities. This led to this nonnative species aggressively kicking native species out of their nests. Luckily this has only caused notable decline in one species, but it can be a problem for local populations and is certainly an issue no one wants to become worse.

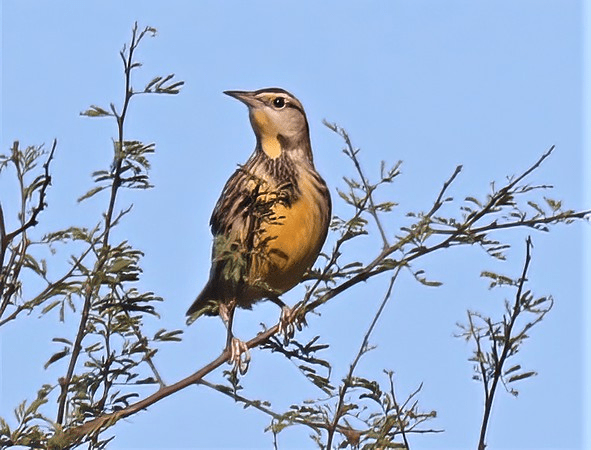

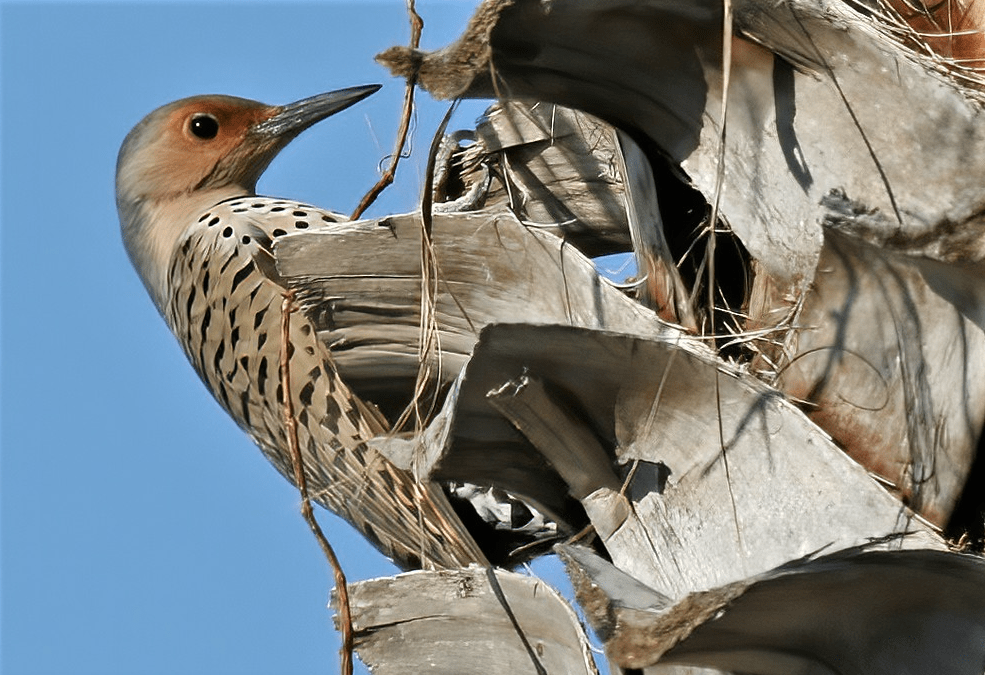

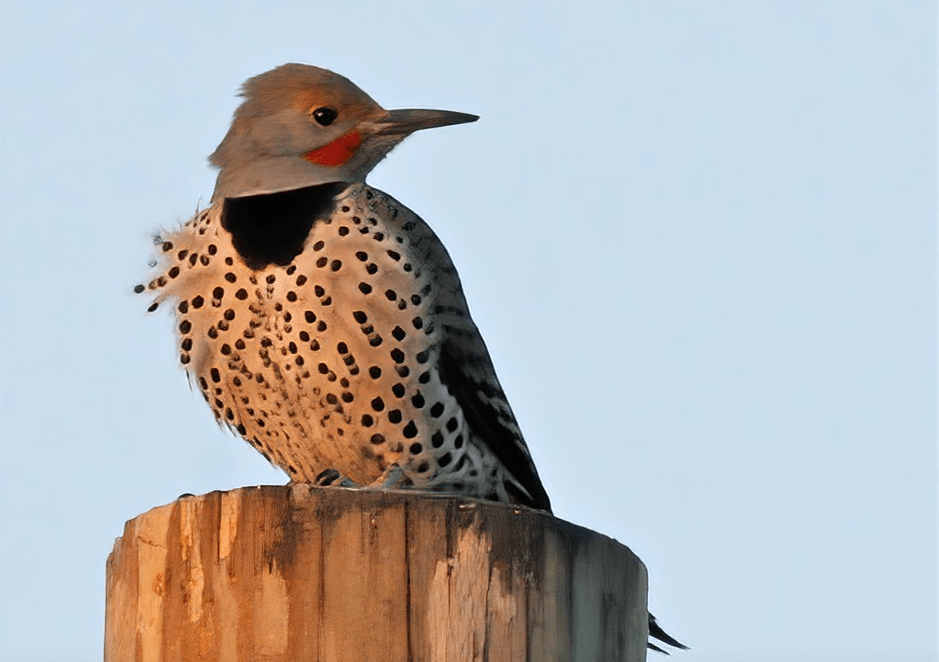

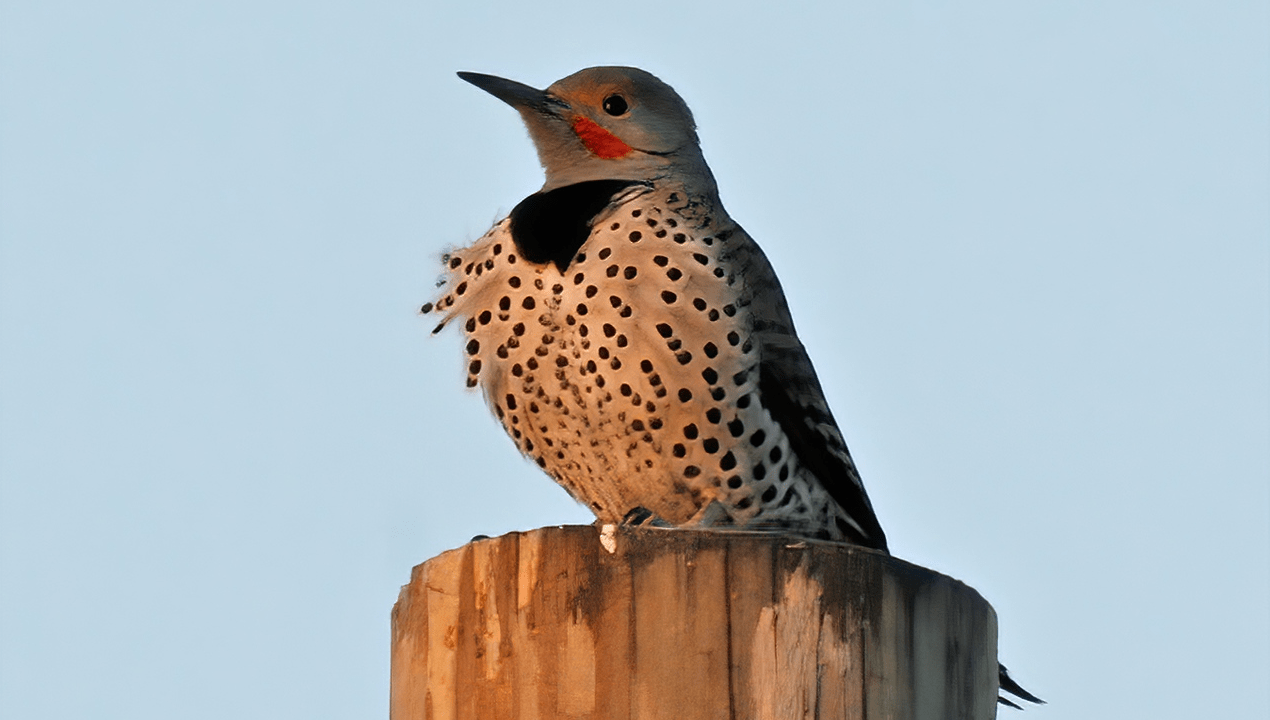

Our next Grassland bird is one that you may not expect as it is, paradoxically, a species of woodpecker.

Seeing a bird hop-shuffling along the ground with is head buried in the grass, you might expect it to be a kind of sparrow, or maybe even a blackbird or grackle. Imagine your surprise then when it isn’t any of those but is in fact a woodpecker!

This ‘black sheep’ of a woodpecker is the Northern Flicker (Colaptes auratus). A rather interesting bird by most accounts, it bears a speckled front with black mutton-chop like plumage coming from the corners of its beak, and when it takes flight the undersides of its wings are an intense yellow. This is a basic description of one of the two forms, or morphs, of this species, the other having red chops and orange underwings. While these two morphs will breed, it is most likely that all you will see is the yellow-barred (yellow- underwing) variety here.

But why on earth is a woodpecker on the ground? Well, they have adapted to forage for insects like ants that live among the grass, hopping along and using their slightly curved bills to probe for a delicious and probably crunchy insect meal. Not to worry though, the classification of woodpecker is still very apt, as these birds do indeed create cavities in trees.

Within these cavities they make in the all-important dead tree, they are relatively safe form most of their would-be predators, though they will sometimes be aggressively annexed from their nests by our last bird, the European Starling. The Flickers can re-nest after a hostile Starling takeover, but it is likely to be a less successful attempt.

Having to go find another nest and feeding out in open grasslands leaves them at risk of being hunted by a raptor that may be a bit smaller than they are, a risk that is increased as they must move from new nest site to new nest site.

It’s here that we come full circle to our first grassland bird; the American Kestrel, a predator that will predate the woodpecker who made the nesting cavity just as much as the the Starling that took it over.

Grasslands are crucial for the survival of many bird species. This is meant to be a small look into the lives of grassland birds, and I hope it illustrates some bit of the connectedness of the species we may find around us. Though they have been classified as grassland birds here, it is important to see their need for more than one habitat to live. Grasslands provide them with ample food and nesting material when they are healthy, but they need forests too in order to have places to nest and ways to evade predators or the elements.